MOUNTAIN OUTLAW MAGAZINE

by Tyler Allen

Click the picture to view the PDF or right-click and choose “Save Link As” to save it to your desktop for easier viewing

NORTHWEST TRAVEL MAGAZINE

by Herbert David & Don Burgess

Click the picture to view the PDF or right-click and choose “Save Link As” to save it to your desktop for easier viewing

THE RIVER WILD

by Jeff Rennicke

July/August 1996 Issue – National Geographic Traveler

Idaho is a state wild at its heart. Central Idaho – home to the Selway, a river called the wildest in the lower 48 states – is a maze of pine-robed mountain ranges, untrailed canyons, creeks and rivers humming through their valleys. The view from any ridgetop carries that slow ache of distance. It is a wildness that touches everything and everyone who comes here.

Idaho is a state wild at its heart. Central Idaho – home to the Selway, a river called the wildest in the lower 48 states – is a maze of pine-robed mountain ranges, untrailed canyons, creeks and rivers humming through their valleys. The view from any ridgetop carries that slow ache of distance. It is a wildness that touches everything and everyone who comes here.

Just ask Marie Smith. One morning Marie, who runs the Three Rivers Resort, where the Selway and the Lochsa join to form the Clearwater River, sat at her desk , her Airedale puppy Lochsa Louie at her feet, gnawing on a bone. When she heard a gurgling sound, she looked up just in time to see a mountain lion stride into the doorway, snatch the dog, and vanish. “We were getting pretty attached to that puppy, too,” she says.

Lewis and Clark felt the wildness. When the two explorers crossed what is now the Montana-Idaho border in 1805 and sized up the rugged country surrounding the Salmon and Selway Rivers, they turned north for Lolo Pass. Almost 200 years later, much of that impassable feeling remains. The National Wilderness Preservation System, begun in 1964, made the 1.3 million acre Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness one of its first protected areas. When Congress was looking to initiate the 1968 National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, it looked first to the Selway. “This is as wild a country as there is,” says Bob Stewart, who wrangled strings of packhorses through the Selway wilderness for a decade before taking up shuttle driving for raft trips, “a hundred miles of solid nothin’.”

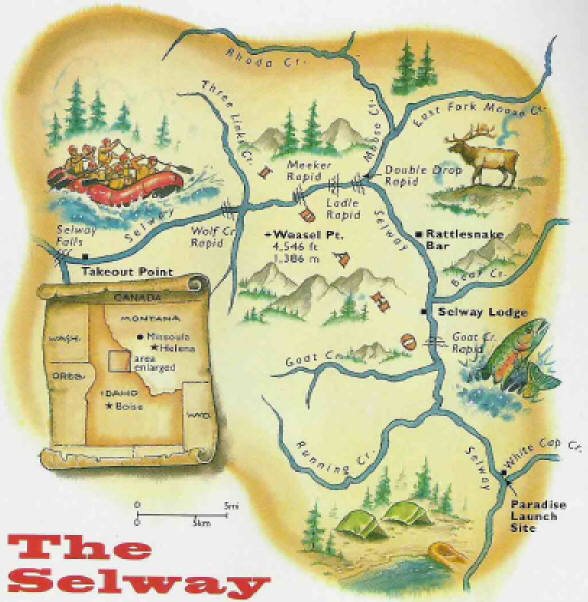

One of the best ways to put yourself in the middle of that “solid nothin'” is to raft the Selway River. But that’s not as easy as it sounds. To preserve the wildness, the U.S. Forest Service, which manages the river, allows only one party a day to launch its rafts. Competition for the 78 launch permits granted each season is intense. With the swarm of applications received, the chance of getting a permit is just one in thirty, making a Selway raft trip one of the most coveted white-water experiences in the country.

Photographer Mike Melford and I were lucky enough to find two empty spaces on a trip with Northwest River Company, one of only three commercial rafting outfits with permits to run the river.

Photographer Mike Melford and I were lucky enough to find two empty spaces on a trip with Northwest River Company, one of only three commercial rafting outfits with permits to run the river.

Doug Tims, owner of the Boise-based company, is a man with a southern drawl and a western soul. He has the tan of someone who rows rafts for a living, yet retains the clean-cut neatness of the insurance salesman he was back home in Mississippi. After years of wearing out vans on coffee-swilling road trips to run western rivers during short vacations, Doug loaded up yet another van with his wife and two daughters and moved west permanently in 1982.

“I wasn’t lucky enough to be born here,” he says, “but I was darn sure smart enough to move here.” On the advice of another boatman, he purchased a Selway rafting business without ever having seen the river himself. A risky move, he admits, “But.” he said to me the night before our trip, “after the next five days, you tell me if you think I made the right decision.”

In a hailstorm on the first day on the river, his cigar too damp to stay lit, he may be having second thoughts, But the next morning with the sun glowing orange on the ponderosa pines and our four urethane rafts – sky blue, yellow, orange and dark blue – drifting on the water like an inflated rainbow, Doug has the swagger of a man who harbors few doubts about anything. “If the Selway ain’t pretty.” he says with a grin and his slow southern cadence, “then grits ain’t groceries, eggs ain’t poultry, and Mona Lisa was a man!”

All 16 of us survived the storm unscathed and emerge looking refreshed, wilder somehow, as if one good rainstorm has washed the city off of us. Like many commercial trips, we are a mixed group. There is a father and daughter from Idaho, a father and son from Chicago, several doctors, a trio of computer salesmen, and others. We are all eager to get a taste of the famous Selway white-water – 45 named rapids Class II or higher (number denotes difficulty, with VI the highest rating) in just 47 miles, rapids with names like Holy Smokes, Galloping Gertie, Ping Pong Alley, and No Slouch. We don’t have long to wait.

All 16 of us survived the storm unscathed and emerge looking refreshed, wilder somehow, as if one good rainstorm has washed the city off of us. Like many commercial trips, we are a mixed group. There is a father and daughter from Idaho, a father and son from Chicago, several doctors, a trio of computer salesmen, and others. We are all eager to get a taste of the famous Selway white-water – 45 named rapids Class II or higher (number denotes difficulty, with VI the highest rating) in just 47 miles, rapids with names like Holy Smokes, Galloping Gertie, Ping Pong Alley, and No Slouch. We don’t have long to wait.

“Goat Creek is a Boatman’s Rapid,” Doug is saying about our first big white water of the trip. “You dance through it, just dance.” But not every dance goes smoothly. “Last trip, at higher water, we had a boatman flip a raft in here, his first flip in 16 years.” No one was hurt, but an $800 water filter was lost, not to mention a bit of pride.

After the buildup, our run at Goat Creek seems tame. Below we spend a long time searching for signs of the lost gear, recovering some beer cans, a glove, an American flag (the flip occurred on the Fourth of July). But there is no sign of the expensive stuff. “Oh well,” Doug says, “Call it an offering to the river gods.”

A few miles below the rapid, we drift up on one of the only signs of civilization on the river: a collection of cabins known as Selway Lodge. First homesteaded in 1898, this is the only working lodge on this stretch of the river, a place to fish, hike, ride or watch wildlife. ” We had 42 elk with babies on the salt lick the other day,” owner Pat Millington told me when I called her after the trip. “People were counting and counting. They couldn’t believe how many there were.” And bears. “Bears like mad,” she said, “like mad, especially in the fall.”

With no road access, the Selway Lodge is reachable only by river and by air. With no television or telephones, it prides itself on its unparalleled solitude. Even guests are kept to a minimum. “We don’t want more than 12 guests at a time,” Pat says. And even then she insists that bookings are taken only every other week, leaving the lodge open only to friends and staff the rest of the time. “We deserve a chance to enjoy some Selway peace and quiet, too,” she laughs.

Out of deference to peace and quiet, both our own and the guests’, we don’t stop at the lodge, just waiving to a family sitting on the porch until we disappear around the bend.

Despite the Selway’s reputation for white water, the upper stretch is relatively calm. We drift in silence for hours, only the river saying “shhhhhh” and the sound of a hermit thrush calling from the shadows. “Whenever a man hears it,” Thoreau said of the thrush’s song, he is young and Nature is in her spring.”

The calm of the quiet water has followed us to shore. At camp on a stretch of pine-shaded sand called Rattlesnake Bar, rafter Hyde Tucker is snoring in his tent. Scott is hitting stones into the river with a stick of driftwood. Several others are fly-fishing for trout. After steaks and salmon on the grill with a river chilled Chardonnay, we will scramble up to the trail in the dark to see the full moon shining on the water. All part of the fine art of doing nothing – and doing it very well. “Pace,” Doug says, leaning back in his lawn chair set near the river’s edge, “is everything.”

The calm of the quiet water has followed us to shore. At camp on a stretch of pine-shaded sand called Rattlesnake Bar, rafter Hyde Tucker is snoring in his tent. Scott is hitting stones into the river with a stick of driftwood. Several others are fly-fishing for trout. After steaks and salmon on the grill with a river chilled Chardonnay, we will scramble up to the trail in the dark to see the full moon shining on the water. All part of the fine art of doing nothing – and doing it very well. “Pace,” Doug says, leaning back in his lawn chair set near the river’s edge, “is everything.”

That pace changes quickly downstream. “Brenda, grab your dad,” Doug shouts over the roar as the raft bounces through Double Drop. Hyde Tucker is dangling precariously out of the raft, held only by his daughter’s arm pulling him back in. “I was fine until the boat made a quick lateral movement,” he says later. “and then I was just hanging there helpless out over the water. I was glad,” he adds in his typical understated style, “to end up back in the boat.”

We’ve entered, on our third day, a section of the river the boatmen call Moose Juice. Here Moose Creek, a tributary almost as big as the Selway itself, enters the river, nearly doubling the flow. The river, which elsewhere drops an average of 28 feet per mile, seems to fall off a cliff below Moose Creek, dropping 150 feet and rumbling through ten rapids in a span of just three miles. This is the heart of the Selway’s power, a place where the air rings with the sound of falling water.

Some of the rapids – Bad Ass, Puzzle Creek, Mary Jane – are just piles of waves that break over your head like fireworks, playgrounds of water and rock. Chris Norborg, a physician on his first river trip, sits in the front of a raft, dropping into a rapid with both arms straight up to the sky. Mike rows his raft, calculating how many elephants rushing by per second it would take to match the power of the river at this spot – “10,000 cubic feet of water per second, times 62.5 pounds per cubic foot flow of water, divided by 10,000 pounds per elephant – that’s 62 elephants per second.”

Some of the rapids – Bad Ass, Puzzle Creek, Mary Jane – are just piles of waves that break over your head like fireworks, playgrounds of water and rock. Chris Norborg, a physician on his first river trip, sits in the front of a raft, dropping into a rapid with both arms straight up to the sky. Mike rows his raft, calculating how many elephants rushing by per second it would take to match the power of the river at this spot – “10,000 cubic feet of water per second, times 62.5 pounds per cubic foot flow of water, divided by 10,000 pounds per elephant – that’s 62 elephants per second.”

Talk of elephants stops at Ladle Rapid. A nervousness moves in as thick as morning fog when you pull ashore to scout the way.

Extremely high water, inexperience, and lack of proper equipment can all make the Selway a dangerous river. Even with medium flows such as we have today, state-of-the-art rafts, and the more than 175 runs of the Selway among Doug and his boatmen, there is always an element of chance in running rapids. Rock and moving water is an unpredictable combination. for a long time we stand on the rocks overlooking the rapid, the boatmen pointing and shouting, discussing each wave, each rock.

“I’m going to pull back down that chute of dark water there,” Doug says finally, pointing, “spin in the still water below, hit the next drop straight, then move left before that last big drop.” He stops a moment, looking first at me, then back at the river. “Theoretically,” he adds.

Our rafts drift in the pool, waiting our turn to run. No one is talking, We check and recheck our life jackets, the grip on our paddles. If a person was prone to second thoughts, I think to myself in the nervous silence, now would be a good time to think them.

Instead I look for diversions – counting the shades of green in the hillside pines, trying to remember the Latin name of the flowers, pink as the inside of an ear, that line both shores. I watch an osprey flying downriver, oblivious to the maelstrom we are about to be pitched into. With just a few beats of its wings, the osprey makes it look so easy. As the boat finally drops into the rapid and the first wave rises like a fist in front of us, I feel the muscles in my arms tighten, involuntarily, as if wishing for wings.

But wings aren’t needed. The boats bounce through the rapids cleanly, leaving us soaked but safe, and exhilarated. “Welcome to the Alive Below Ladle Club,” Doug shouts as the last boat pulls to shore for lunch. Somehow the watermelon tastes sweeter, the beer a little colder downstream of a rapid as big as Ladle

The pace slows again a few miles below Ladle Rapid. On the quiet water a different kind of wildness settles over the trip. In the deep Selway solitude the days take on a feeling of endlessness, of freedom. We have seen no one else on the river – and lost the belief that we ever will.

In that kind of solitude there is time to sit and wonder at cedar trees eight centuries old, to search the shallows for the shadows of fish, to hike off a meal.

One morning I bushwhack up the ridge behind camp after breakfast. There in the damp woods I find a Pacific yew whose bark yields a substance that could lead to breakthroughs in the fight against cancer. The sight of it reminds me that wilderness is more than just thrills and rapids, and makes me think of Ron Dorn, back at camp. A physician at the Mountain States Tumor Institute in Boise, Ron told me one day along the river that he comes on trips like this “to put things back in perspective” again after dealing daily with the pressures of life and death. There are elk tracks in the mud.

The view from the ridge is endless, the peaks still untangling themselves from the morning mist. I let my eyes trace the horizon, wondering what tracks might be among the trees on that hillside. Although there hasn’t been confirmed sighting in years, some say grizzlies still roam these mountains. Wolves, reintroduced into Idaho at the same time as the more publicized Yellowstone release, have been sighted near the waters of the Selway and may someday be heard again along this river.

We need places with that kind of possibility in them, the possibility of bighorn on the cliffs, moose in the meadow, deer. Or of a wild cutthroat trout rising to a fly.

We need places with that kind of possibility in them, the possibility of bighorn on the cliffs, moose in the meadow, deer. Or of a wild cutthroat trout rising to a fly.

As the river winds toward its finish, attention turns from white water to fishing. On the last day I drift with Doug Tims and Michael Melford, who have challenged each other to a fishing contest. a kind of modern-day duel with fly rods. As they whip the water, filling the air with coils of line, Doug, who carries a laminated copy of the Wilderness Act and quotes it like poetry, talks about his role on the Selway River.

“One of our missions is to introduce people to wilderness values. This river speaks volumes about what it means for a place to be wild,” he says, glancing from me to the river and back. “There has to be somewhere people can get a true wilderness experience, and you can still find that here on the Selway. We should do whatever it takes to insure it remains that way.”

A mile from the takeout, both Michael and Doug have caught and released four trout. Now the fishing gets serious.

The talking stops. Each works his side of the raft, intent as herons on the water. One last perfect cast, one last chance. Their arms cock. The rods snap overhead, graceful curves of line arc out over the water, the flies settle gently as leaves on the water. And ….. well, the best fish stories always leave a little to the imagination.

At the takeout, shuttle vans and people; a party of packers water their stock at the river, the horses looking as if they are kissing their own reflections in the water. Our solitude breaks like an eggshell, but the memory of it lingers. Doug and I shake hands on the trip. “You made the right decision,” I say. “About what fly to cast back there?” he asks, knowing full well that is not what I am talking about.

And then he grins.

Jeff Rennicke, a former professional river guide, has written several books and many articles about wild rivers in the West.